Posted on February 5, 2025

One solution to address chronic absenteeism lies in increasing districts' capacity to address the whole-child and turn their schools into resource hubs.

TO: Members of the Senate Education Committee

FROM: Isaiah Fudge, Director of Positive Youth Development Policy and Advocacy, Advocates for Children of New Jersey

DATE: January 30, 2025

RE: Chronic Absenteeism

Good morning, members of the Senate Education Committee, thank you for the opportunity to present

testimony on chronic absenteeism.

I am Isaiah Fudge, Director of Positive Youth Development Policy and Advocacy with Advocates for

Children of New Jersey. I am a former High School English Teacher; and a former Resource Specialist for people returning from incarceration. Before graduating from a poverty stricken public school system in NJ, I dropped out of one. And, I am now a father to a middle school student attending a New Jersey public school in a more affluent community than I grew up in. I understand, first hand, the complexities surrounding chronic absenteeism.

In 2014, the Department of Education suggested ACNJ review the chronic absenteeism numbers throughout the state and bring some attention to the issue. In the 2013-14 school year, there were 125,000 K-12 students or 10% of the state’s total student population, who were identified as chronically absent using the definition of missing 10% or more of excused or unexcused school days. Twenty-three percent of kindergarteners and 27% of 12th graders were missing 10% or more days of school. There were 177 districts in NJ having 10% or more of their students chronically absent. Their average was 16%, or 76,000 students. Many of these districts measured the issue by looking at their daily attendance numbers which they reported to the state Department of Education. The report got a lot of attention and really brought the issue to the forefront at the state and local levels. ACNJ published three state reports, as well as two Newark chronic absenteeism reports: one focused on the early learning years and one on the high school years. By the third statewide report, we saw 8000 fewer NJ students who were chronically absent, with fewer districts making the list.

At the same time, ACNJ pushed for legislation to define chronic absenteeism, require districts to publish their chronic absenteeism numbers in their school report cards and require some kind of corrective action plan involving feedback from parents for districts with 10% or more chronic absenteeism rates. Governor Murphy signed the bill into law in 2018.

Chronic absenteeism has surged since the pandemic. As we wrestle with this issue nationally, New Jersey’s current 16.6% chronic absenteeism rate ranks better than other states. But, as of 2022-23, there were 1,371,921 students enrolled in our schools. That means 219,507 students missed 18 or more days of school that year. I haven’t done the math yet, but this equates to a lot of missed time for education, for our youth, for various reasons.

Causes

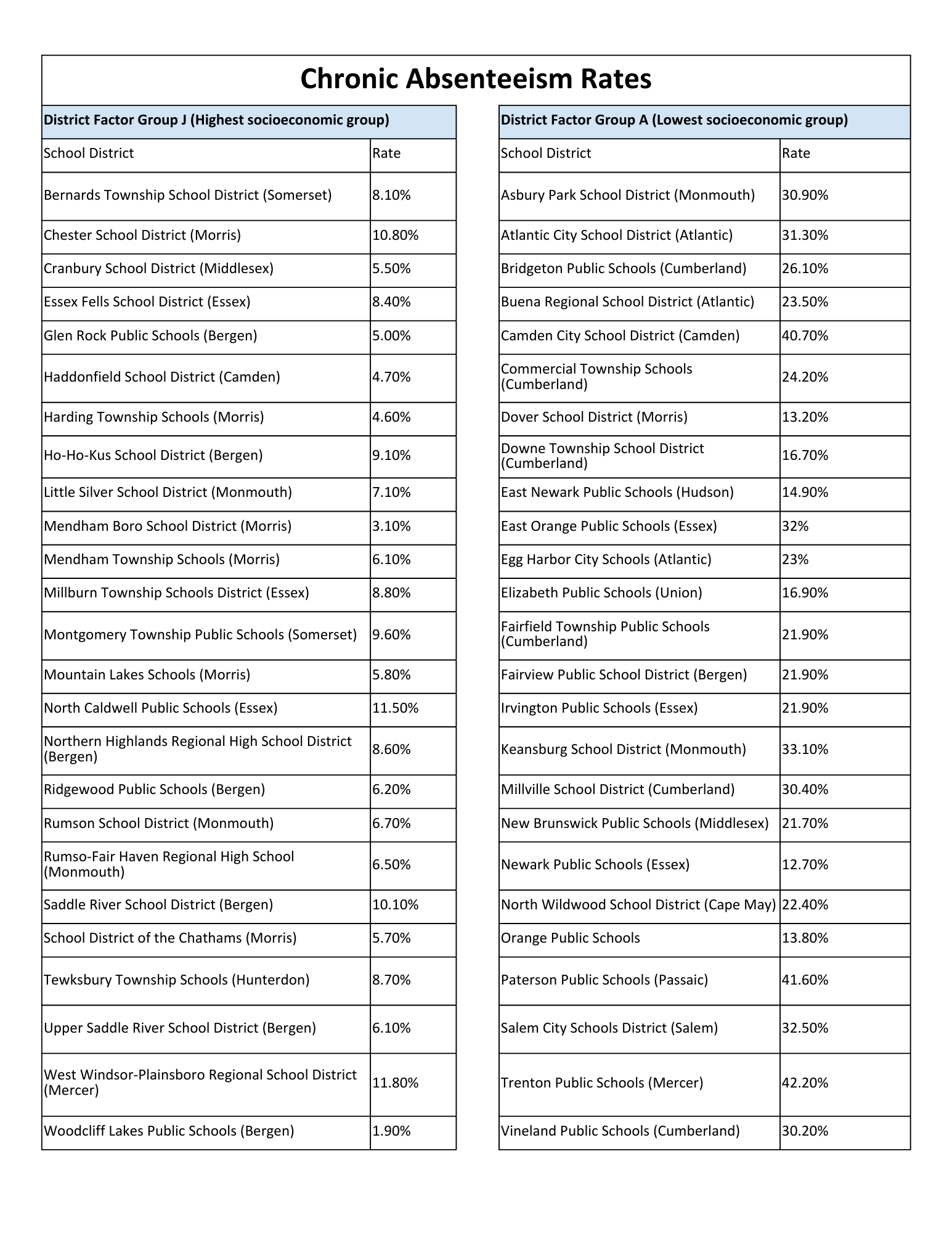

One of the biggest causes of chronic absenteeism relates to poverty, or socioeconomic factors. Lack of child care, transportation, food, and other essentials often disrupt daily life for families who don’t consistently have access to the resources they need. When juxtaposing 52 school districts in the state–the 26 wealthiest and 26 of the poorest–we see that the wealthiest districts have a chronic absenteeism rate lower than the state average (often much lower), and the 26 poor districts usually have a rate that’s higher. For example, Haddonfield schools, one of the wealthiest districts in the state, has a 4.7% chronic absenteeism rate, while Camden schools, one of the poorest districts, has a rate of 40.7%. The poverty surrounding the schools in the poorest districts creates barriers to youth attendance.

And, once students get to school they are often met with a climate that pushes them out. For youth in poverty, those that don’t have clean clothes, or food, or soap and water, avoiding school becomes a real option, especially when harassment or bullying might await them. According to 2022-23 NJ Department of Education data, there were over 9,000 reported incidents of harassment, bullying, or intimidation.

This often leads to violence, and other issues. There were over 14,000 reports of violence, and 61,000 total suspensions, with over 44,000 of those being out of school suspensions. School personnel also reported incidents to police over 10,000 times. For perspective, pre-pandemic, in 2019-20, we were at just under 5,000 times where incidents were reported to police, and just under 40,000 total suspensions.

We also know that teachers are leaving the profession at higher rates for several reasons, but especially because of the climate within many of our schools. When we look at the role of socio economics in the lives of our students and combine that with the impact COVID has had on everyone’s mental health, we see that our schools have become environments that many people are avoiding.

Another cause for the high rate is lack of awareness about chronic absenteeism. Many students and families just don’t know enough about this issue to even recognize it as an issue. I have not examined the policies of all 593 school districts, but I would venture to say that many, if not all of them have information available to students and families on chronic absenteeism. However, we have to ask ourselves how is that information being made available to them? When is it made available to them? If it’s online, how do we know that families without internet are able to access it? Basically, we have to question whether or not we are doing enough to ensure students and families are well-informed about this issue.

Solutions

One solution lies in increasing districts' capacity to address the whole-child and turn their schools into resource hubs. The families in the schools in the wealthiest districts tend to consistently be able to meet the foundational needs of their kids. Meeting those needs consistently creates conditions for them to attend school regularly. S2243 and S2528 would create similar opportunities for families of lower socio-economic statuses. The full-service community school model presents a way for poorer districts to meet their students’ needs. The model involves integrating student supports and engaging students and families, among other best practices. What is great about this approach is that, when implemented appropriately, students and families become involved in their own advocacy, and essentially help select the resources needed for their particular circumstances.

Unfortunately, to this point, only 4 districts have formal full-service community school arrangements. But, there are schools and districts incorporating components of the model and they are making progress around chronic absenteeism. In Orange Public Schools, Rosa Parks Community Schools reported a 7.4% chronic absenteeism rate. The district itself is at 13.8%. Dover Public Schools is at 13.2% district-wide. Bringing resources into schools brings kids back to school. You can’t control the poverty around the schools, but you can control the poverty within them. We must invest in schools’ capacity to address the needs of their students.

We must also commit to bringing more socio-emotional character development resources into our schools. This can occur through training staff to incorporate best practices, through building schools’ capacity to address safety issues by leveraging the community; through situating more mental health resources in schools; or through a combination of all 3. Clayton Public Schools is a district that isn’t part of the poorest group of districts, but sits close to that group. Yet, they have been intentional about incorporating socio-emotional development work and report an 8.9% rate as a result. In Elizabeth Public Schools, where the rate has gone from 19.4% to 16.9% in the past two years, there is focus on creating and sustaining mental health partnerships with the community. And, In Newark, the district has leveraged Violence Intervention professionals to ensure students are able to get to school safely. I have not seen any proposed Senate legislation that unites all three 3, but on the Assembly side, there’s A622, which establishes the Safe Schools and Communities Violence Prevention and Response Act. A Senate version of this legislation would set the foundation for ultimately enabling districts to onboard staff that can holistically address school culture and climate for students, and everyone else in the buildings.

Or, we can repurpose Attendance Counselors across districts. I saw a job description that required the Counselor “Serve on [a] Truancy Task Force. . . patrolling neighborhoods. . . with the . . .Police Department in order to transport truant students to the Task Force location; transport students from Truancy Task Force location to the school where the student is registered” This approach only entrenches the work done in schools to create poor climates. Instead, Attendance Counselors should be taking a proactive, upstream approach to preventing chronic absenteeism. Newark Public Schools recognizes this. In several of their schools, Attendance Counselors facilitate wrap-around support to ensure students and families’ needs are met, rather than acting as an extension of law enforcement. As a result, Newark reported a reduction in district-wide chronic absenteeism last year, and is at 12.7%, below the state average.

If there were more information about chronic absenteeism, students and families would be able to make better decisions about attending school. A simple solution to this would be to monitor how and when schools are sharing this information. We must outline to schools the need for students and families to receive this information upfront and ongoingly, and in a variety of ways. And, we must require schools update all electronic and print policies, rulebooks and guidelines to obviously reflect 1. the definition of chronic absenteeism; 2. the pathway for potential chronic absenteeism remediation; 3. the consequences of chronic absenteeism, both personally and related to school.

Again, I want to thank you for the opportunity to provide testimony here, today. I am looking forward to working with everyone to continue to combat this issue. Should you have any questions feel free to contact me at ifudge@acnj.org.